Providing an Oasis in Legal Deserts

November 18, 2024The term “desert” can describe a region of extremely high or low temperatures with scarce vegetation. According to Mary Irvine ’12, executive director of North Carolina Interest on Lawyers’ Trust Accounts (NC IOLTA), in social contexts, “desert” describes a geographic area that does not have sufficient resources of a particular quantity or quality to meet the needs of those who live there. Food deserts describe locations without access to affordable, quality food options; childcare deserts describe areas without sufficient slots for daycare to effectively serve children in need of care.

“From my perspective, the phrase ‘legal deserts’ is a useful tool to start a conversation about how we can improve available legal resources and build awareness around the lack of access to legal services, particularly for low-income individuals and families in rural areas, and the serious consequences that lack of access presents for our justice system,” says Irvine.

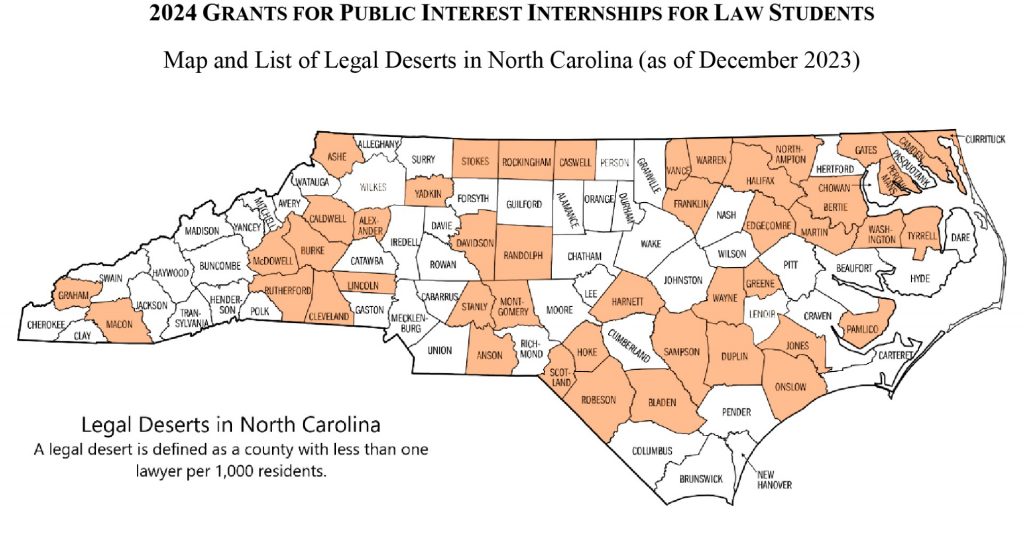

Legal deserts are defined as geographic areas with less than one attorney per 1,000 residents. According to research conducted by the American Bar Association, 1,300 counties in the United States meet this definition, including many counties with no attorneys at all. In North Carolina, 45 out of 100 counties have less than one attorney per 1,000 residents. Irvine notes, “Without attorneys who practice nearby, rural residents face barriers accessing legal assistance and support. For low-income residents, those barriers increase manyfold. For example, residents in a legal desert without sufficient financial resources to meet their needs will be even less able to access legal services if they don’t have childcare, a reliable car, or consistent internet access.”

To address the lack of access to legal services, NC IOLTA serves as the philanthropic arm of the North Carolina State Bar by funding high-quality legal assistance. Working directly with lawyers and financial institutions across our state, NC IOLTA utilizes interest earned on lawyers’ trust accounts to fund grants to organizations that provide legal aid, with awards totaling more than $122 million since the program’s inception in 1983.

As part of a new effort, NC IOLTA provides up to $50,000 per year to each accredited North Carolina law school to support students. These public interest grants allow students to be compensated even if the organization they work for cannot pay summer legal interns. Qualifying public interest placements include nonprofit organizations that provide free civil legal services to low-income individuals, public defender and district attorney offices, and courts across the state where the students are working under the supervision of judges. To qualify, the summer internship must be primarily focused on serving the residents of counties designated as a legal desert.

At UNC School of Law, students must apply for a grant and meet specific criteria to be placed and receive compensation.

“These grants and the work of the students have a profound impact on the communities they serve,” says Devi Patel, former director of public interest advising at Carolina Law. “The principle that ‘justice delayed is justice denied’ is particularly relevant in areas where a shortage of attorneys leads to significant delays in due process.”

Patel notes that individuals in legal deserts may wait weeks or months without receiving meaningful representation, creating a true crisis. “In these communities, low-income and marginalized groups face significant barriers to accessing legal support, resulting in prolonged legal battles and unjust outcomes,” she says.

As part of this summer’s grant program, second-year law student Aleah Wordsworth worked with the North Carolina Office of Special Counsel (OSC), which provides representation to individuals who have been involuntarily committed to mental hospitals. She assisted OSC staff in Burke County, N.C. by conducting legal research into potential constitutional violations of patients, collaborating with another intern in drafting the attorney manual for OSC, and assisting in the creation of the informational brochure for patients who have been involuntarily committed.

According to Wordsworth, many patients in Burke County are unaware of their rights upon admission to a mental hospital. The creation of an informational brochure informing patients of their legal rights helps them make informed decisions about whether to proceed with a hearing.

“Carolina Law has provided me with an education in legal research that has greatly assisted me in my internship experience,” says Wordsworth. “I was able to research necessary case law and statutes that assisted in providing information to patients and attorneys.”

When reflecting on her own time at Carolina Law, Irvine recalls utilizing various supports offered to students, from dedicated public interest advising to student organizations focused on issues that mattered to her, to a robust and nationally recognized Pro Bono Program that offered regular opportunities for students to learn by supporting underprivileged communities.

Irvine’s internship during her first year connected her with Advocates for Children’s Services, now called the Right to Education Project, at Legal Aid of North Carolina. This project represents children across the state to ensure their access to education. “I worked with experienced, committed advocates and served kids in counties across the state, from Forsyth to Bladen to Vance to many in between,” she recalled of her first-year summer. “I was able to grow in my career path through the law school’s dedication of resources to support students with goals to work in the public interest, so I know the difference this support can make.”

Second-year law student Max Parker spent their summer working for Legal Aid of North Carolina in their Smoky Mountain offices in Sylva and Murphy, N.C. They assisted on cases in a variety of legal practice areas, including domestic violence, housing, public benefits, consumer protection, and criminal record expunction.

“What stayed with me the most is the ways that legal issues are interconnected. When someone has a conviction on their record, it often prevents them from being able to access safe and stable housing. Then, that person has no choice but to rent from a bad-actor landlord, who takes advantage of them,” they said. “Similarly, if someone doesn’t have access to legal services to help them prepare a will, they might die intestate, and the ownership of their family home is divided up as heirproperty, and eventually becomes vulnerable to predatory action.”

For Patel, the biggest obstacle to sending students to legal deserts is the lack of funding and resources.

“Many law students are eager to gain experience and make a meaningful impact in underserved communities, but they often face financial constraints that make it difficult to take unpaid or low-paid positions. Additionally, logistical challenges such as housing options, transportation issues, and the need for community support and adequate mentorship in these remote areas can further complicate placements,” says Patel.

She believes addressing these obstacles requires a concerted effort to provide financial support, logistical assistance, and robust infrastructure to ensure that students can effectively contribute to addressing the legal needs in these underserved communities. Fortunately, NC IOLTA grants provide the much-needed infusion of resources to help bridge the gap.

This story was originally featured in the September 2024 issue of Carolina Law Magazine